Performance analysis of multithreaded applications.

05 Oct 2019

Contents:

- Benchmark under the test

- Performance scaling

- CPU utilization

- Synchronization overhead

- Profiling multithreaded apps

- Per-thread view

- Using strace tool

- Optimizing multithreaded apps

Subscribe to my newsletter, support me on Patreon or by PayPal donation.

Modern CPUs are getting more and more cores each year. As of 2019 you can buy fresh x86 server processor which will have more than 50 cores! And even mid-range desktop with 8 execution threads will not be surprising. Usually the question is how to find the workload to feed those hungry guys.

Most of the articles in my blog so far were focused on the performance of a single core, completely ignoring the entire spectrum of multithreaded applications (MT app). I decided to fill this gap and write a beginner-friendly article showing how one can quickly jump into analyzing performance of the MT app. Sure, there is a lot of details which is impossible to cover in one article. Here I just want to touch ground on performance analysis of MT apps, give you the checklist and the set of tools which you can use. But be sure, there will be more of it on my blog, just stay tuned.

This is a series of articles. Other parts of the series can be found here:

- Performance analysis of multithreaded applications (this article).

- How to find expensive locks in multithreaded application.

- Detecting false sharing with Data Address Profiling.

As usual, I provide my articles with examples, so let me start with the benchmark which we will be working on.

Benchmark under the test

For better illustration I had few constraints in mind when choosing the benchmark: 1

- It should have explicit parallelism using

pthread/std::thread(no OpenMP). - It does not scale with the amount of threads added. Work is not split, equally between threads.

- Of course, open source and free.

I took h264dec benchmark from the Starbench parallel benchmark suite. This benchmark decodes H.264 raw videos and uses pthread library for managing threads.

One can run this benchmark like this:

$ ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t <number of threads> -o output.file

In this benchmark there is one main thread (mostly idle), one thread that reads the input, configurable number of worker threads (that do decoding) and one thread that writes the output.

Performance scaling

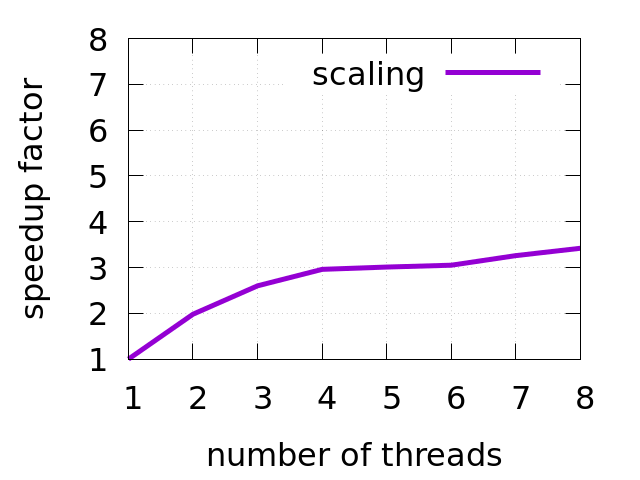

First thing in MT app that needs to be estimated is how it scales as we throw more cores/threads to it. In fact, this is the most important metric of how successful the future of the app will be. The chart below shows the scaling of h264dec benchmark. My CPU (Intel Core i5-8259U) has 4 cores/8 threads, so I took upper bound as 8 threads. Notice, that after using 4 threads, performance doesn’t scale much.

This is very useful information when you try to model performance of the workload. For example, when you estimate what HW you need for the task you are trying to solve. Looking at this picture, I will better choose less cores but higher frequency of a single core. 2

Sometimes we could be asked what is the minimal system configuration that can handle a certain workload. When the application scales linearly (i.e. when threads work on independent piece of data and do not require synchronization) you can provide rough estimation pretty easily. Just run the workload in a single thread and measure the number of cycles executed. Then you can select CPU with specific number of cores and frequency to meet your latency/throughput goals. Situation gets tricky however, when performance of the app doesn’t scale well. Here you can’t rely on IPC anymore (see later), since one thread can be busy and show high utilization, but in fact all it was doing is just spinning on a lock. There is more information on capacity planning in the book Systems Performance by Brendan Gregg.

CPU utilization

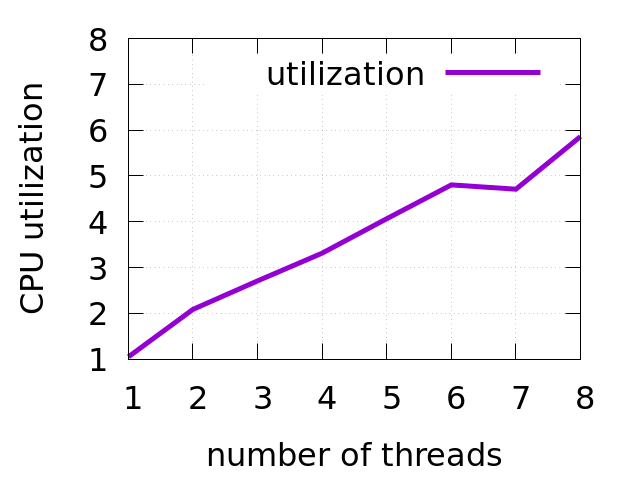

Next important metric is CPU utilization 3. It can tell you how much threads on average were busy doing something. Note, that it is not necessarily useful work. It can be just spinning. Below you can see the chart for h264dec benchmark.

For example, when having 5 worker threads for the workload, on average only 4 were busy. I.e. typically, one thread was always sleeping, which limits scaling. This tells that there is some synchronization going between the threads.

Synchronization overhead

To estimate how much overhead is spent on communication between threads we can collect the total number of cycles and instructions:

# 1 worker thread

$ perf stat ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 1 -o output.file -v

261,963,433,544 cycles # 3.766 GHz

485,932,999,948 instructions # 1.85 insn per cycle

66.236645032 seconds time elapsed

66.290561000 seconds user

3.324930000 seconds sys

# 4 worker thread

$ perf stat ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 4 -o output.file -v

272,518,956,365 cycles # 3.479 GHz

523,079,251,733 instructions # 1.92 insn per cycle

23.643595782 seconds time elapsed

73.979057000 seconds user

4.402318000 seconds sys

# 8 worker thread

$ perf stat ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 8 -o output.file -v

453,581,394,912 cycles # 3.410 GHz

661,715,307,682 instructions # 1.46 insn per cycle

22.700304401 seconds time elapsed

128.122821000 seconds user

4.883838000 seconds sys

There is a couple of interesting things here. First, don’t be confused by the timings for the case with 8 threads. CPU time is more than 5 times bigger than the wall time. It perfectly correlates with CPU utilization.

Second, look at the number of instructions retired for 8 threads case. For 8 worker threads we have 36% more executed instructions than in single-thread which is all can be considered as overhead. All this is likely caused by thread active synchronization (spinning).

Profiling multithreaded apps

To do analysis on a source code level let’s run the profiler on it: 4

# 1 worker thread

$ perf record -o perf1.data -- ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 1 -o output.file -v

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 10.790 MB perf1.data (282808 samples) ]

# 4 worker thread

$ perf record -o perf4.data -- ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 4 -o output.file -v

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 12.592 MB perf4.data (330029 samples) ]

# 8 worker thread

$ perf record -o perf8.data -- ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 8 -o output.file -v

[ perf record: Captured and wrote 21.239 MB perf8.data (556685 samples) ]

The number of samples correlates with the user time we saw earlier. I.e. the more workers we have the more interrupts profiler needs to do. If we look into the profiles, they will mostly look similar except one function ed_rec_thread:

# 1 worker thread

$ perf report -n -i perf1.data --stdio

# Overhead Samples Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ............ ....... ................ .....................................

0.18% 524 h264dec h264dec [.] ed_rec_thread

# 4 worker thread

$ perf report -n -i perf4.data --stdio

# Overhead Samples Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ............ ....... ................ .....................................

3.62% 11417 h264dec h264dec [.] ed_rec_thread

# 8 worker thread

$ perf report -n -i perf8.data --stdio

# Overhead Samples Command Shared Object Symbol

# ........ ............ ....... ................ .....................................

17.53% 95619 h264dec h264dec [.] ed_rec_thread

Notice how ed_rec_thread function takes much more samples with increasing the number of threads. This is likely the bottleneck that prevents us from scaling further with adding more threads.

Also, this is one of the methods how we can find synchronization bottlenecks in the MT app. By simply comparing profiles for the different number of workers.

And in fact, there is this code in decode_slice_mb function that is inlined into ed_rec_thread:

while (rle->mb_cnt >= rle->prev_line->mb_cnt -1);

where mb_cnt is defined as volatile. So, it is in fact active spinning happens here.

Per-thread view

Linux perf is powerful enough to collect profiles for every thread that is spawn from the main thread of the process. If you want to look inside the execution of a single thread perf let you do this with -s option:

$ perf record -s ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 8 -o output.file -v

Then you can list all the thread IDs along with the number of samples collected for each of them:

$ perf report -n -T

...

# PID TID cycles:ppp

6602 6607 52758679502

6602 6603 487183790

6602 6613 49670283608

6602 6608 51173619921

6602 6604 165362635

6602 6609 38662454026

6602 6610 31375722931

6602 6606 48270267494

6602 6611 53793234480

6602 6612 25640899076

6602 6605 14481176486

Now, if you want to only analyze the samples that were collected for particular software thread, you can do it with --tid option:

$ perf report -T --tid 6607 -n

8.28% 25657 h264dec h264dec [.] decode_cabac_residual_nondc

7.12% 35880 h264dec h264dec [.] put_h264_qpel8_hv_lowpass

6.19% 31430 h264dec h264dec [.] put_h264_qpel8_v_lowpass

5.87% 28874 h264dec h264dec [.] h264_v_loop_filter_luma_c

2.82% 10105 h264dec h264dec [.] ff_h264_decode_mb_cabac

1.19% 4525 h264dec h264dec [.] get_cabac_noinline

If you are a lucky owner of Intel Vtune Amplifier, you can use it’s nice GUI to do the filtering and zooming into particular thread and point in time.

When you nailed down the thread that is causing you troubles and you don’t care much about the other threads, you can profile only one thread by attaching to it with perf:

perf record -t <TID>

Using strace tool

Another thing which I use regularly is strace tool:

$ strace -tt -ff -T -o strace-dump -- ./h264dec -i park_joy_2160p.h264 -t 8 -o output.file

This will generate syscall dumps per running thread with precise time stamps and duration for each syscall. We can further process individual dump file to extract lots of interesting information from it. For example:

# Total time spent by parser thread waiting for mutex to unlock

$ grep futex strace-dump.3740 > futex.dump

$ sed -i 's/.*<//g' futex.dump

$ sed -i 's/>//g' futex.dump

$ paste -s -d+ futex.dump | bc

16.407458

# Total time spent by parser thread on reading input from the file

$ grep read strace-dump.3740 > read.dump

$ sed -i 's/.*<//g' read.dump

$ sed -i 's/>//g' read.dump

$ paste -s -d+ read.dump | bc

2.179850

Considering total running time of the thread is 21 seconds, almost 80% of the time this thread was blocked. Since this thread provides input for the worker threads, that’s likely another thing that limits performance scaling of the benchmark.

Optimizing multithreaded apps

When dealing with single-threaded application, optimizing one portion of the program usually yields positive results on performance5. However, it’s not necessary the case for multithreaded applications. And in fact, it can be very hard to predict. That’s where coz profiler might help. I wasn’t able to extract any useful information from using it, but it was the first time I tried it, so maybe I was doing something wrong.

If your application scales well or threads work on independent piece of input, then you may see a proportional increase in performance as a result of your optimizations. In this case it’s easier to do performance analysis of the application running on a single thread. There is a good chance that optimizations that are valid for single thread will scale well. 6

Top-Down Methodology, our best friend in finding michroarchitectural issues, will become even better in new Intel CPU generations. See the presentation by Ahmad Yasin for more details.

However, there are performance problems that are specific to multithreading. In future articles I will touch the topics of lock contention, false sharing and more. Stay tuned!

-

I’m planning to run the perf tuning contest with some MT benchmark that has constraints that I mentioned. If you know a good one, let me know. ↩

-

As a rule of thumb, the higher the core count the lower the frequency of a single core. You can find that client CPUs (desktops) usually have much higher frequencies than server CPUs. But server CPUs have much more cores. ↩

-

CPU utilization can be calculated as

CPU_CLK_UNHALTED.REF_TSC / TSC. ↩ -

To further improve the analysis you can add call stacks to the picture by adding

--call-graph lbrto yourperf recordcommand line. ↩ -

If the application makes forward progress all the time. ↩

-

It may not always be the case. For example, resources that are shared between threads/cores (like caches) can limit scaling. Also compute bound benchmarks tend to scale only up to the number of physical (not logical) cores, since two sibling HW threads share the same execution engine. ↩

All content on Easyperf blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License