How to find expensive locks in multithreaded application.

12 Oct 2019

Contents:

- Benchmark under the test

- Find expensive synchronization with Vtune.

- Find expensive synchronization with perf.

Subscribe to my newsletter, support me on Patreon or by PayPal donation.

This article is a continuation of a first part of what hopefully will become a series of posts about performance analysis of multithreaded (MT) applications.

Other parts of the series can be found here:

- Performance analysis of multithreaded applications.

- How to find expensive locks in multithreaded application (this article).

- Detecting false sharing with Data Address Profiling.

As discussed in first part, usually the reason that prevents MT app from scaling linearly is communication between threads. Today I will try to expand this topic in more details.

In particular, the question I will try to answer today is: how to find the code where threads spend the most time waiting and which code paths lead to it?

Having answer to this question is essential on the way to fully utilize all of the compute power in the system. Especially if you’re just starting out with a new benchmark or application. If you know your multithreaded application very well, it gives you great advantage over someone who just starting. I often work with new applications and benchmarks and I just can’t allow myself to spend few days studying the source code of it. So, for me it’s essential to be able to get up to full speed as soon as possible. That’s why I need to know what are the bottlenecks in the application so I can study only a small portion, that is required to understand the issue. And I need support from the tools to tell me this critical information.

But even if you think you know your application well, you may be surprised how wrong your intuition can be. It’s always good to measure and prove all your hypothesis.

Benchmark under the test

I choose x264 benchmark from Phoronix test suite for this article. This is a simple multithreaded test of the x264 encoder with configurable number of threads. What is important for us here is that it doesn’t scale linearly, meaning that there is some communication between threads happening. One can find instructions how to build and run the benchmark here. I built it with debug information (./configure --extra-cflags=-g) and run with 8 worker threads on Ubuntu 18.04 + Intel Core i5-8259U:

$ ./x264 -o /dev/null --slow --threads 8 Bosphorus_1920x1080_120fps_420_8bit_YUV.y4m

Some important metrics:

- Wall time: 17.4 seconds.

- Total CPU time: 88 seconds.

- Total Wait time: 90.6 seconds.

It’s interesting actually and deserves a little explanation. If we sum up CPU time and Wait time we will have 178.6 seconds which is greater than the possible CPU time on 4core/8threads CPU. In this case if the CPU utilization would be 100% we would have maximum 17.4 * 8 = 139.2 seconds CPU time. However, don’t be confused about it. Because the total number of threads that were spawned is 11 (not 8), 3 threads were always waiting. This all accumulates into a what could be perceived as a big amount of compute power wasted, however it’s not necessary that bad. That’s why Vtune extensively operates with the metric of “Effective CPU utilization” which can be calculated as ∑i=1,ThreadsCount(CPUTime(i)), sum of CPU time for all the threads, which is 63% in our case. 1

Find expensive synchronization with Vtune.

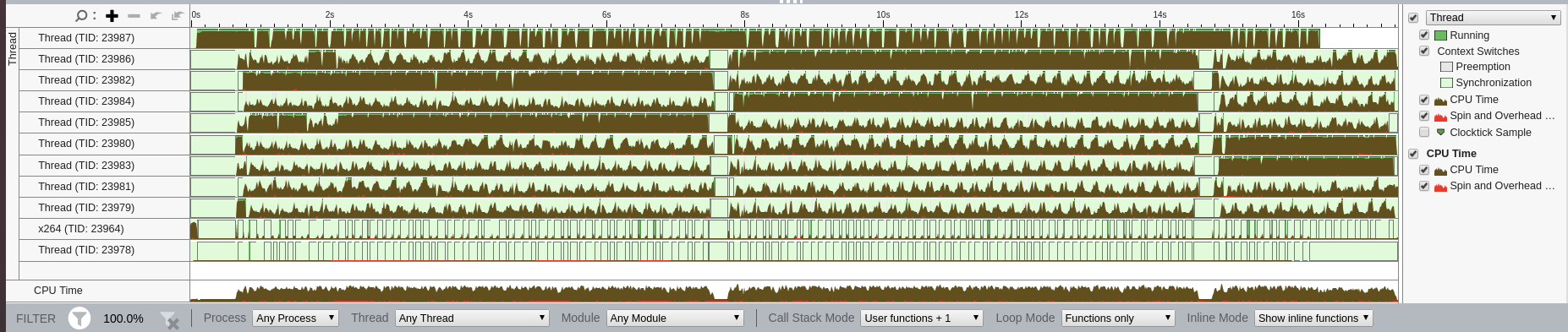

Vtune has impressive collection of predefined types of analysis, from which threading analysis2 is of particular interest for us. I like to look into the platform view to get basic understanding of the application. I simply can’t refrain myself from posting screenshots from Vtune, because they are so useful.

Platform view (clickable):

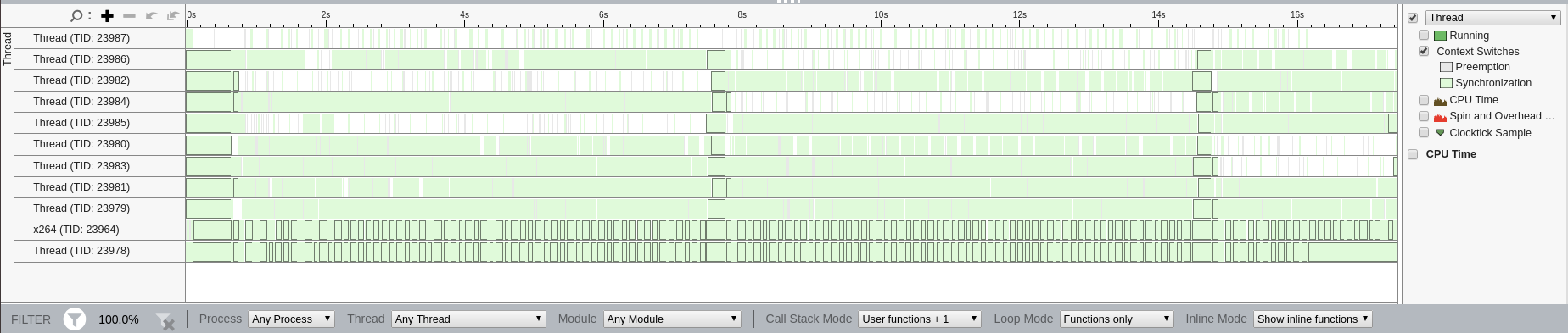

Context switches view (clickable):

Context switches view (clickable):

It’s very interesting to look at this timeline. We can immediately build mental model of how our threads run over time. We can spot the main thread (TID: 23964), possibly producer thread (TID: 23987) and 8 consumer threads (TIDs: 23979-23986). We can see that at the same time only 3 threads had high CPU utilization (for the period from 1sec - 7sec they were TID: 23987, 23982, 23985). Also, Vtune’s powerful GUI allows us to zoom in and see what particular thread was doing in some period of time.

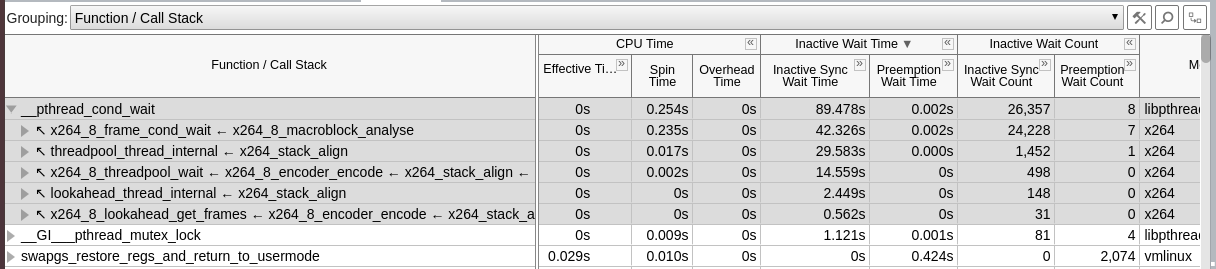

If we now take a look at the bottom-up view and sort by “Inactive Wait Time” we will see the functions that contributed to the most Wait time.

But what’s more interesting is that we can see the most frequent path that lead to waiting on conditional variable: __pthread_cond_wait <- x264_8_frame_cond_wait <- x264_8_macroblock_analyse (47% of wait time).

By knowing this information you can immediately, jump into the source of those x264_ functions and study the reason behind the locks and possible ways to make thread communication in this place more efficient. I don’t claim that it will be necessary an easy road and there is no guarantee that you will find the way to make it better. But at least you can save yourself several hours of studying the application logic.

Find expensive synchronization with perf. 3

In order to have similar information with Linux perf tool you need to do something like this:

$ sudo perf record -s -e sched:sched_switch -g --call-graph dwarf -- ./x264 -o /dev/null --slow --threads 8 Bosphorus_1920x1080_120fps_420_8bit_YUV.y4m

Unfortunately, this requires root access, since we introspect into the kernel scheduler events. Here is the output you might see:4

$ sudo perf report -n --stdio --no-call-graph -T

# Samples: 28K of event 'sched:sched_switch'

# Event count (approx.): 28295

# Children Self Samples Trace output

# ........ ...... ....... ......................................................................

2.18% 2.18% 617 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21712 prev_prio=130 ==> next_comm=swapper/3 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

2.14% 2.14% 606 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21709 prev_prio=130 ==> next_comm=swapper/6 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

2.14% 2.14% 605 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21711 prev_prio=130 ==> next_comm=swapper/7 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

2.01% 2.01% 570 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21709 prev_prio=130 ==> next_comm=swapper/7 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

1.99% 1.99% 564 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21709 prev_prio=130 ==> next_comm=swapper/0 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

1.98% 1.98% 559 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21709 prev_prio=130 ==> next_comm=swapper/5 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

...

Notice, this output doesn’t tell us the total time spent waiting. It just tells us the most frequent places where context switches happened (see detailed output later). You may also see that this output is combined for all the threads. Meaning that the same path can lead to the lock for multiple threads. And indeed, the same hot path that triggered the lock was more expensive for thread with TID: 21712 (617 samples) than for TID: 21709 (606 samples).

For this example, we can calculate what percentage of all context switches were caused by any thread waiting on a conditional variable:

$ sudo perf report -n --stdio > stdio.sched

$ grep __pthread_cond_wait stdio.sched -w -B10 | grep prev_comm=x264 | sed 's/%.*//' | awk '{i+=$1} END {printf("%.2f%%\n",i)}'

85.09%

Also, if you go all the way down in the output from perf report command above, in the end you will find total number of sched:sched_switch samples per thread: 5

# PID TID sched:sched_switch

21704 21714 208

21704 21709 4047

21704 21708 3399

21704 21712 3291

21704 21706 1743

21704 21710 1324

21704 21711 1361

21704 21713 1161

21704 21707 168

21704 21705 220

Let’s focus on thread with TID 21709 as it was context switched most often. This is an example of what you can see in the output:

$ sudo perf report -n --stdio --tid=21709

# Children Self Samples Trace output

# ........ ........ ............ ..................................................................................................................

#

2.14% 2.14% 606 prev_comm=x264 prev_pid=21709 prev_prio=130 prev_state=S ==> next_comm=swapper/6 next_pid=0 next_prio=120

|

---0xffffffffffffffff

|

--2.09%--x264_8_macroblock_analyse

mb_analyse_init (inlined)

x264_8_frame_cond_wait

|

--2.09%--__pthread_cond_wait (inlined)

__pthread_cond_wait_common (inlined)

futex_wait_cancelable (inlined)

entry_SYSCALL_64

do_syscall_64

__x64_sys_futex

do_futex

futex_wait

futex_wait_queue_me

schedule

__sched_text_start

If you want to trace all the context switches (not only that were caused by waiting on a lock) you can do it with:

$ sudo perf trace -e sched:*switch/max-stack=10/ ./x264 -o /dev/null --slow --threads 8 Bosphorus_1920x1080_120fps_420_8bit_YUV.y4m &> trace.dump

That’s all for now. Stay tuned for more posts in this series about performance analysis of multithreaded applications.

-

Alternatively, we can calculate it as “Total CPU time/ Max CPU time” or

88 / 139.2 = 63%. ↩ -

Make sure you checked the box that says “Collect stacks”. Otherwise you will not have information which function in the application triggered thread lock. ↩

-

The output is trimmed a little bit in order to fit on the screen. ↩

-

This is not the absolute number of context switches. ↩

All content on Easyperf blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License