Machine Programming. What if computers would program themselves?

24 Jan 2021

Contents:

- A high-level vision

- Code similarity analysis

- Detecting performance regressions

- Enhance debugging

- Conclusion

Subscribe to my newsletter, support me on Patreon or by PayPal donation.

Today, I would like to write about a novel idea called Machine Programming (MP). I was following research in this area during the last year or so. I think it has the potential to revolutionize the way how we develop software. MP ignite a special interest in me since at that time I was writing my book. I was thinking to myself, like “Oh-oh, if MP would be working full-steam today, my book shouldn’t have existed”.

So, what is Machine Programming? It is a bold idea to automate the entire software development cycle, including writing the code, testing, debugging, and maintaining it. MP is driven by MIT, Berkley, Intel, Google, and other big names and certainly gains traction in the industry.

The main driving force for this initiative is a futuristic vision that everyone would be able to program computers. Right now, it is a privilege of only 1% of the population in the world. That’s right, 99% of the population on the planet cannot program machines. This could become possible if we enable machines to understand human intention without the need to write the actual code. In the MP vision, the machine will do all the tedious work, including creating the code and verifying that it accomplishes the goal.

Secondly, the world becomes increasingly heterogeneous, which I talk about in my previous post. The truth is that no one can program that many devices. The initiatives like OneAPI may definitely help here by providing a simple standardized way of programming various devices. But still, there will be a lot of complexity for creating an efficient implementation of that API. An example I have in mind is: at Intel, we have many performance libraries that provide highly tuned routines for math primitives, linear algebra, memory management, etc. This is a tone of code that is written by experts and is very complicated. Automation has to come in some form to ease the production and maintaining the lower-layer code.

Machine Programming is largely applying Machine Learning (ML) techniques. But ML usually allows some inaccuracy in results. If a face recognition feature on your iPhone fails once per month, we could live with that, no one will die. But with MP, we can’t allow the machine to misinterpret human’s intention. So, Machine Programming also uses formal methods to verify its correctness.

A high-level vision

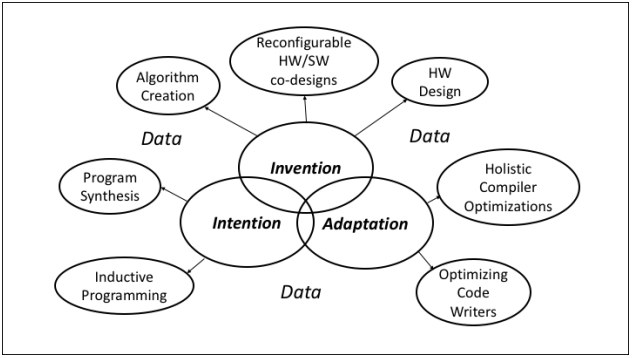

At a high level, Machine Programming relies on three pillars, as denoted in the original visionary paper1:

- Intention. It is an interface between a human and a machine. It allows a human to specify their intention in any form. It could be a UML diagram, pseudocode, or even natural language. Regardless of the format, the machine should be able to adapt. It’s like you communicate your idea to the machine. And once it understood what you want from it, it says: “Ok, give me a few hours, I’ll build it for you”. Taking into consideration Elon’s Musk NeuraLink technology, this isn’t something that is out of reach.

- Invention. Once the intention is understood, the machine creates all the necessary components to achieve the desired goal, like algorithms and data structures, the need for network communication, etc. It is still relatively high-level and the “design” created by the machine is SW and HW agnostic.

- Adaptation. The third step in this process is to specialize the “design” (a result of the invention step) to the particular HW and SW ecosystem, e.g. create an implementation, like compile it down to the machine code, optimize and verify that it is working.

The bold idea of MP is that humans should only specify the intention. The rest should be handled by the machine, like choosing the best algorithm and data structure, implement the code and verify it against the human intention. The research in the MP area is nowhere near having a generalized solution to a problem described previously. But there is early evidence that it may be possible. The people that drive the MP research showed that they could solve the issue for a very small and constrained problem. You can find more details in the papers referenced at the end of the article.

Code similarity analysis

Personally, I’m interested in MP as it promises to revolutionize performance engineering. The problem today is that there is a Ninja Gap that can be defined as a performance gap between the code written by casual developers and the code written by performance experts. Let it not surprise you that the ninja gap can be as high as 10x or even more. If we can “mine” the code written by performance ninjas and recommend it for casual developers to reuse, the gap can be conquered. To effectively suggest the right code candidate to reuse, we need to be able to classify the snippet of code and to tell if two different snippets of code are similar. This would be nice if we could have a collection of golden code, classified by the semantics of the code. The machine will go like: “Oh, I see you’re sorting the array of small-sized objects. Here is the best implementation of it, tuned for the target configuration”.

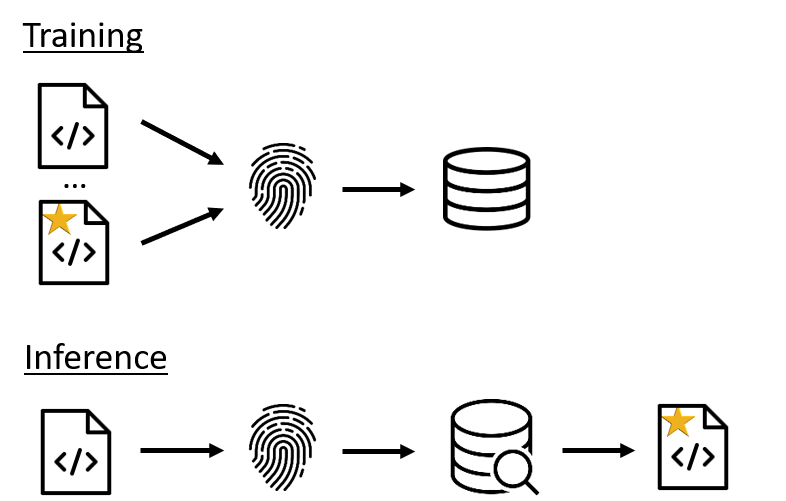

The ability to classify the code, opens many new opportunities, like building recommendation systems, that will recommend the code that might be better. On a very high-level, we need to train the database of golden code, where each class of code snippets will have its own fingerprint. Then, we will be able to query this golden database for recommendations. The core challenge here is to extract the semantics of the code, for example, being able to tell: “this code does sorting or matrix multiplication, etc”.

Code similarity analysis is still in the early stages, but there is a growing body of research in this area. The problem can be stated as the following: given 2 pieces of code, we try to detect if they do a similar thing, even if their implementation is different. The latest state-of-the-art tools that address code similarity problem are Aroma and MISM:

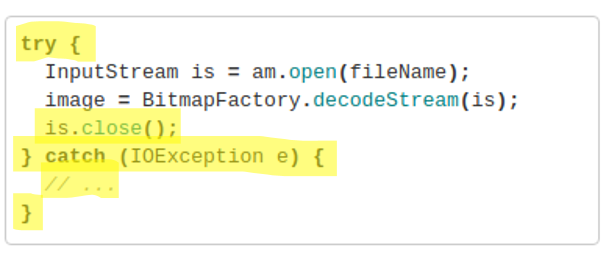

Aroma2. Aroma is a code recommendation system that takes a code snippet and recommends extensions for the snippet. The intuition behind Aroma is that programmers often write code that may have already been written. Aroma leverages a codebase of functions and recommends extensions in a live setting. Aroma introduces the simplified parse tree (SPT) - a tree structure to represent a code snippet. Unlike an AST, an SPT is not language-specific and enables code similarity comparison across various programming languages. To compute the similarity score of two code snippets, Aroma extracts binary feature vectors from SPTs and calculate their dot product. Below is the example that the paper authors give in their paper. Original Java code doesn’t properly close the input stream and handles any potential IOException. Code lines recommended by Aroma are highlighted in yellow.

The paper authors evaluated Aroma by indexing over 2 million Java methods and performed searches with code snippets chosen from the popular Stack Overflow questions. Think of it as you would search on Stack Overflow how to properly close an input stream in Java. Results showed that Aroma was able to provide useful recommendations for a majority of these snippets.

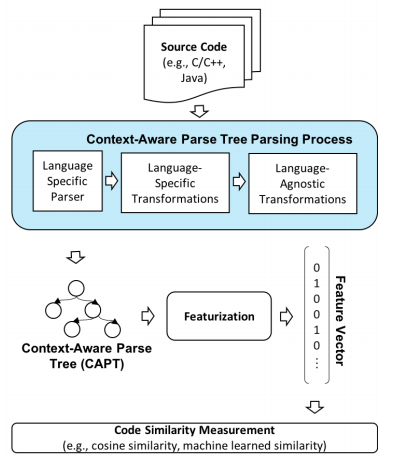

MISIM3. MISIM is a novel code similarity tool, which claims to be more accurate than Aroma. MISIM is based on Context-Aware Parse Tree (CAPT4), which enhances SPT by providing a richer level of semantic representation. CAPT provides additional support for language-specific techniques, and language-agnostic techniques for removing syntactically-present but semantically irrelevant features.

Then MISIM employs a neural-based code similarity scoring algorithm to compute the similarity score of two input programs. According to the research paper, an experimental evaluation showed that MISIM outperforms three other state-of-the-art code similarity systems (including Aroma) usually by a large factor (up to 43x).

Detecting performance regressions

Another area where MP is showing significant progress in detecting performance regressions. It is becoming a trend that SW vendors try to increase the frequency of deployments. Unfortunately, this doesn’t automatically imply that SW products become better with each new release. Software performance regressions are defects that are erroneously introduced into software as it evolves from one version to the next. Performance regressions can be treated as anomalies that represent deviations from the normal behavior of a program.

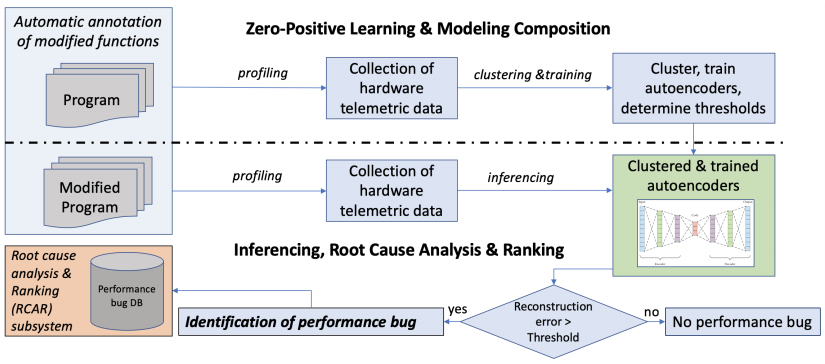

AutoPerf5 is a new framework for software performance regression diagnostics, which fuses multiple state-of-the-art techniques from hardware telemetry and machine learning to create a unique solution to the problem. First, AutoPerf leverages hardware performance counters (HWPCs) to collect fine-grained information about run-time executions of a program. Then it utilizes zero-positive learning (ZPL6) for anomaly detection, and k-means clustering to build a general and practical tool based on collected data. AutoPerf can learn to diagnose potentially any type of regression that can be captured by HWPCs, with minimal supervision. The overview of Autoperf workflow is shown in the figure below.

The authors of the tool showed that this design can effectively diagnose some of the most complex software performance bugs, like those hidden in parallel programs. However, even the tool can detect performance regressions, it still cannot identify the root cause of such bugs yet.

Enhance debugging

The last interesting research that I would like to share today aims to enhance SW debugging, which has been shown to utilize at least 50% (!) of developers’ time. The high-level vision of Machine Programming with regards to debugging is to provide suggestions about a potential bug. The general goal is to have a machine operate like: “We don’t know for sure, but based on analyzing one million similar code snippets, we think there is a bug in your code. Here is the suggested diff how you can fix it. Do you want to apply the change?”

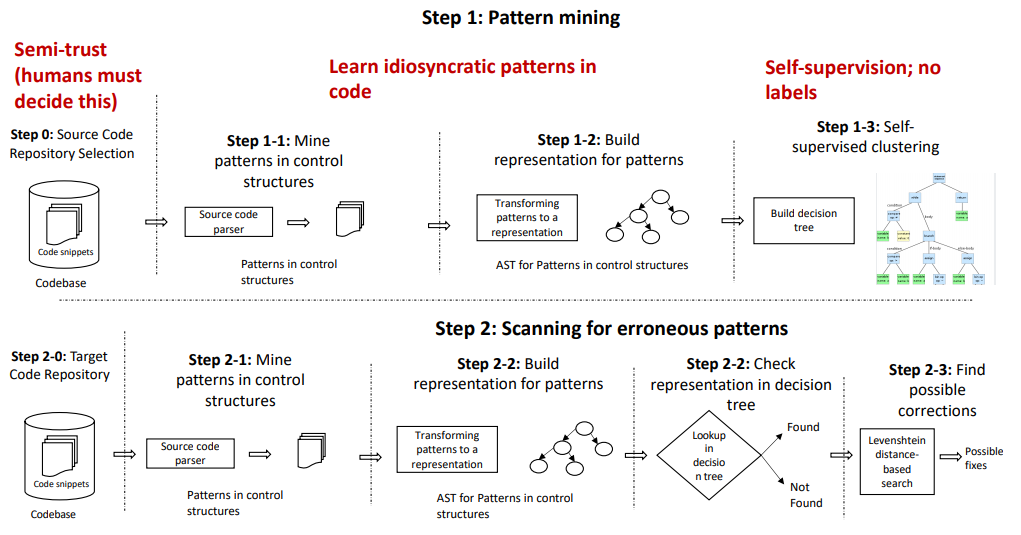

Again, there is early evidence that it might be possible. There is a recent paper about ControlFlag7, the tool that detects possible idiosyncratic pattern violations in the code. Researchers used ControlFlag to analyze 6000 GitHub repositories with at least 100 stars, which is considered as high-quality software. ControlFlag then utilizes all the learned data to scan the target code to find potential bugs. That way, the authors of the paper were able to find real bugs in such well-known software packages like CURL and OpenSSL.

In the figure below you can find the overview of the ControlFlag algorithm. ControlFlag consists of two main phases: pattern mining and scanning. The pattern mining phase consists of learning the common and uncommon idiosyncratic coding patterns found in the user-specified GitHub repositories, which, when complete, generates a precedence dictionary that contains acceptable and unacceptable idiosyncratic patterns. The scanning phase consists of analyzing a given source code repository against the learned idiosyncratic patterns dictionary. When anomalous patterns are identified, ControlFlag notifies the user and provides them with possible alternatives.

Conclusion

I think Machine Programming has the potential to disrupt the way we write software. We can envision a future where computers will participate directly in the creation of software. Although, I don’t know if it is for good or for bad. There is some fear that some jobs can be eliminated. But also, some jobs will be eliminated for good. It is too early to say what MP can bring.

Machine Programming makes big leaps in research, thanks to progress in Machine Learning. Also, today we have a lot of open code repositories that can be used for training, which also drives MP forward. Anyway, I would say, it is at least a 20-year problem. There is early evidence that one day we will have machines create SW for themselves, but right now we are nowhere near having a generalized solution to that problem.

Referenced papers:

-

Gottschlich, et al. (2018). The Three Pillars of Machine-Based Programming. CoRR, abs/1803.07244. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1803.07244. ↩

-

Luan, et al. (2019). Aroma: Code Recommendation via Structural Code Search. Proc. ACM Program. Lang., 3 (OOPSLA) URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3360578. ↩

-

Fangke, et al. (2020). MISIM: A Novel Code Similarity System. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.05265. ↩

-

Fangke, et al. (2020). Context-Aware Parse Trees. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.11118. ↩

-

Alam, et al. (2020). A Zero-Positive Learning Approach for Diagnosing Software Performance Regressions. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.07536. ↩

-

Tae Jun Lee, et al. (2018). Greenhouse: A Zero-Positive Machine Learning System for Time-Series Anomaly Detection. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.03168. ↩

-

Niranjan Hasabnis, & Justin Gottschlich. (2021). ControlFlag: A Self-supervised Idiosyncratic Pattern Detection System for Software Control Structures. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.03616. ↩

All content on Easyperf blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License