What optimizations you can expect from CPU?

22 Apr 2018

Contents:

Subscribe to my newsletter, support me on Patreon or by PayPal donation.

Compilers are known for doing all sorts of cool optimizations on the source code, generating very efficient assembly code. You can expect that there will be no useless computations in the compiled code. Even if you leave those inefficiencies, most major compilers will optimize everything away. Moreover, compilers are aware (to some degree) about microarchitectural details of the target CPU. So, it may seems that compiler is the one who is in charge for performance, but it’s not.

Modern high-end CPUs are also known to be really greedy when it comes for performance, and they also do amazing job at running assembly code super-fast. In this post I tried to show what optimizations you can rely on, and what patterns are still beyond CPU capabilities.

Zero Idiom

From Agner’s Fog microarchitecture.pdf:

The processor recognizes that certain instructions are independent of the prior value of the register if the two operand registers are the same. An instruction that subtracts a register from itself will always give zero, regardless of the previous value of the register. This is traditionally a common way of setting a register to zero. Many modern processors recognize that this instruction doesn’t have to wait for the previous value of the register. What is new in the Sandy Bridge is that it doesn’t even execute this instruction. The register allocater simply allocates a new empty register for the result without even sending it to the execution units. This means that you can do four zeroing instructions per clock cycle without using any execution resources. NOPs are treated in the same efficient way without using any execution unit.

For example:

sub eax, eax

xor eax, eax

To illustrate this I ran 1000 iterations (edi == 1000) of the code below using uarch-bench tool. All experiments I’ve done on Ivy Bridge CPU:

.loop:

xor eax, eax

dec edi

jnz .loop

Results:

Benchmark Cycles UOPS_EXECUTED.CORE UOPS_ISSUED.ANY UOPS_RETIRED.ALL

xor eax, eax 1.02 1.01 2.04 2.00

As always, this tool shows the values for the counters per iteration. Remember, that dec + jnz are MacroFused into one uop, which is the only uop that was executed (utilizing execution units). Read more on this in my blog post about MacroFusion.

Interestingly enough, that on Ivy Bridge mov eax, 0 is not recognized:

Benchmark Cycles UOPS_EXECUTED.CORE UOPS_ISSUED.ANY UOPS_RETIRED.ALL

mov eax, 0 1.02 2.02 2.04 2.00

You can see that 2 uops were executed, meaning that mov instruction also utilized execution units.

Move elimination

Again, from Agner’s Fog microarchitecture.pdf:

An eliminated move has zero latency and does not use any execution port. Zero latency instructions (for example NOP instructions) don’t consume scheduler resources. However, those instructions still consume bandwidth in the decoders and reserve a number of slots in the reorder buffer.

Move elimination is not always successful. It fails when the necessary operands are not ready. But typically, move elimination succeeds in more than 80% of the possible cases. Chained moves can also be eliminated. Move elimination is possible with all 32-bit and 64-bit general purpose registers and all 128-bit and 256-bit vector registers.

Example:

.loop:

add eax,4

mov ebx,eax ; this mov can be eliminated

sub ebx,ecx

dec edi

jnz .loop

I ran 1000 iterations of the loop, and here is what I received:

Benchmark Cycles UOPS_EXECUTED.CORE UOPS_ISSUED.ANY UOPS_RETIRED.ALL

move elimination 1.03 3.02 4.04 4.01

Once again, the number of executed uops is less than the number of issued and retired uops. dec + jnz were MacroFused into one uop and the mov inside the loop was eliminated.

Other experiments

Zeroing instructions and move elimination are well known idioms, but let’s try to check what else patterns can be recognized by the CPU.

Redundant movs

.loop:

mov eax, 1 ; will be eliminated?

mov eax, 2

dec edi

jnz .loop

Now, I want to mention, that compilers will never generate this dumb code (if it’s not a bug in the compiler). Also in embedded world this code can make sense, when you need to write particular sequence of bytes into the microcontroller registers. As before I ran 1000 iterations and indeed CPU silently executes every assembly instruction:

Benchmark Cycles UOPS_EXECUTED.CORE UOPS_ISSUED.ANY UOPS_RETIRED.ALL

mov eax, 1; mov eax, 2 1.02 3.02 3.05 3.00

Substracting zero

.loop:

xor eax, eax

sub ebx, eax ; will be eliminated? (eax is always 0)

dec edi

jnz .loop

Results show that CPU doesn’t recognize that eax is always zero and does subtracting operation on ebx register:

Benchmark Cycles UOPS_EXECUTED.CORE UOPS_ISSUED.ANY UOPS_RETIRED.ALL

implicit sub 0 1.02 2.01 3.04 3.01

In this example, xor eax, eax consumed no execution resources, so that’s where the difference between the number of executed and issued uops comes from. I tried to do explicit subtraction of 0, and it also was not eliminated:

sub ebx, 0 ; execution not eliminated on IvyBridge.

Known comparison

.loop:

mov eax, 0

mov ebx, 0

cmp eax, ebx ; eax and ebx are always equal

jne .exit

dec edi

jnz .loop

.exit:

Results:

Benchmark Cycles UOPS_EXECUTED.CORE UOPS_ISSUED.ANY UOPS_RETIRED.ALL

known comparison 1 2.02 4.05 4.10 4.01

In this example there are 2 mov uops and 2 Macrofused cmp+jump uops, which give total of 4 uops. Each of them utilized execution resources and nothing was eliminated.

Summary

Modern CPU are very powerful at doing computations, but don’t expect miracles from it.

Zeroing instructions and move elimination are implemented using the microarchitectural features, and they require small amount of extra logic in the CPU frontend.

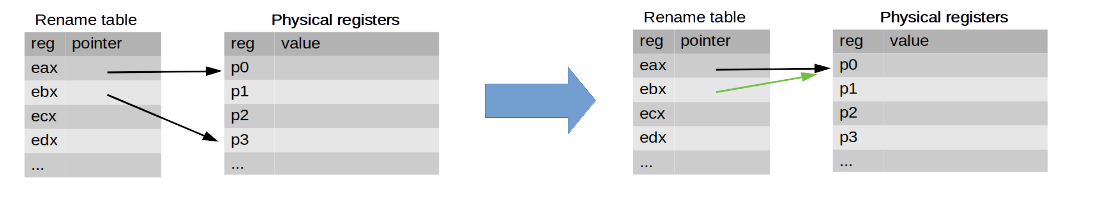

I think that some of the sequences are faster to execute than try to preprocess them in the front-end. For example, the case with redundant movs (see mov eax, 1; mov eax, 2). Mechanism of register renaming and pending register writes works really well here. Trying to identify those 2 instructions with the same destination registers may just not worth the effort.

Last two cases (substracting zero and known comparison) were rather a blind shot. In order to eliminate instructions in question we need to do comparisons of the inputs in the front-end, but it’s a job for a back-end, so we can just schedule them for the execution.

All content on Easyperf blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License